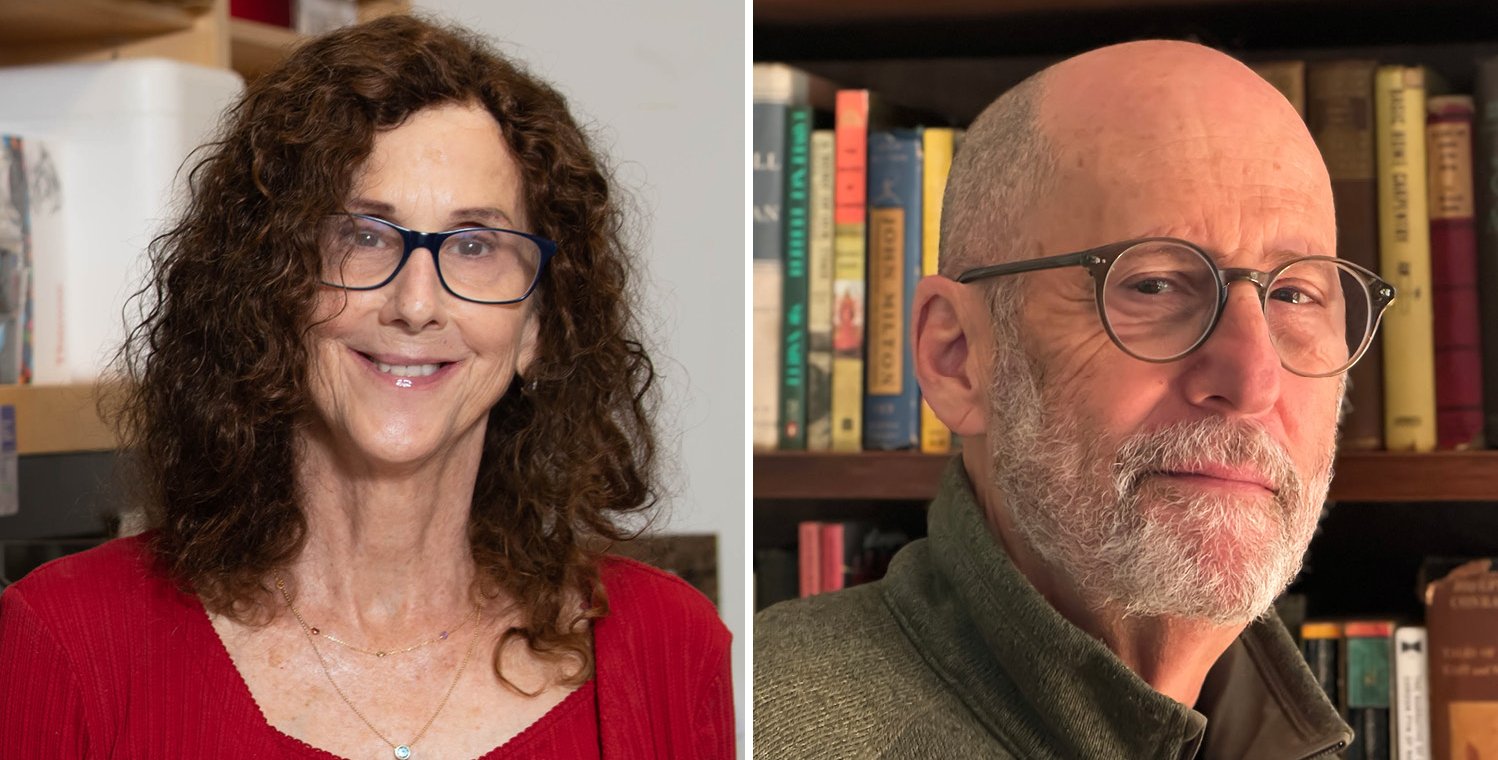

Pamela Björkman and Jim Eisenstein are named Wolf Prize laureates for 2025

Pamela Björkman, the David Baltimore Professor of Biology and Biological Engineering; and Jim Eisenstein, the Frank J. Roshek Professor of Physics and Applied Physics, Emeritus; have each been awarded the Wolf Prize in their respective fields.

According to the Wolf Foundation, the Wolf Prize "acknowledges scientists and artists worldwide for their outstanding achievements in advancing science and the arts for the betterment of humanity."

Björkman, who is also a Merkin Institute Professor, is the recipient of the 2025 Wolf Prize in Medicine "for pioneering innovative strategies to overcome viral defenses through novel antibody-focused approaches." Björkman's award-winning accomplishments, her prize citation states, trace back to her time at Harvard University as a graduate student and postdoc when she first took on the challenge of uncovering the structural basis of T cell recognition of viral and other antigens bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. Her work helped reveal the complicated dance in which T cells, a type of white blood cell that is a key part of the immune system, recognize and kill virally infected cells.

Though particularly relevant to research on HIV, Björkman's work revealed the structure of other MHC-related proteins with a range of different functions, such as the maternal/fetal transfer of antibodies, and the metabolism of iron and fat. Her continued work on HIV immune responses prepared her to take on the challenge of developing vaccines for coronaviruses—including SARS-CoV-2—her most recent work.

"The problem with HIV is that there are so many strains of the virus, and it doesn't do any good to prevent just one strain, especially if you're trying to make a universal vaccine," Björkman explains. "Since the early 2000s we've been working on figuring out how antibodies recognize multiple strains of HIV in cases where they're able to do that. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, we took everything we'd been trying to do with HIV, and to a certain extent with influenza, and started looking at how antibodies from COVID-19 donors recognized the coronavirus spike protein."

This work has enabled Björkman to identify areas of the receptor-binding domain that enable viruses to bind to host cells that are more likely to be conserved across SARS-CoV-2 variants and related animal coronaviruses and, therefore, are able to repel not just one variant of SARS-CoV-2 or related animal viruses, but potentially all of them. "There are many kinds of viruses related to SARS-CoV-2 in animals that have not yet spilled over into humans, but inevitably, they will," Björkman says. "Most current vaccines target only one SARS-CoV-2 variant, whereas the vaccine we developed should elicit antibodies that can repel all SARS-CoV-2–related viruses. We know that it works against SARS-CoV, which spilled over into the human population in the early 2000s, and the vaccine looks poised to protect against all such viruses."

Eisenstein was awarded the 2025 Wolf Prize in Physics along with Moty Heiblum of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and Jainendra Jain of Pennsylvania State University "for advancing our understanding of the surprising properties of two-dimensional electron systems in strong magnetic fields." Heiblum and Eisenstein are experimentalists while Jain is a theorist .

While a two-dimensional electron system may seem obscure, Eisenstein points out that they are in fact ubiquitous in modern electronic devices. In the most refined examples, such systems are so free of impurities and defects that extremely subtle collective quantum mechanical behavior of the electrons can be observed under the appropriate conditions. Examples include the various quantum Hall effects in which, as the Wolf Prize citation notes, electrical current is sometimes carried by bizarre new particles that have a precise fraction of the charge held by an ordinary electron.

Within this area of research, Eisenstein is especially interested in the collective behavior of a pair of two-dimensional electron systems, with one layer placed on top of the other. He and his Caltech research group discovered that at a very low temperature and high magnetic field, electrons in each layer can bind onto the vacancies between electrons (also known as "holes") in the opposite layer. The resulting electron-hole pairs condense into a collective phase with remarkable properties whose detection and study relies on methods invented by Eisenstein.

While the real-world consequences of this research are almost impossible to predict, Eisenstein notes that superconductivity, the poster child for collective electron behavior, was discovered over a hundred years ago by scientists working in a lab just like his. Those researchers, of course, had no inkling that seven decades later their discovery would help revolutionize medical diagnostics by enabling magnetic resonance imaging.

"Receiving the Wolf Prize is a great feeling," Eisenstein says. "It's a sign from the community that the work that I and my two colleagues have done is important enough to merit this recognition."

Björkman expresses similar sentiments, and also her surprise to learn about the award via a phone call from Israel, where the Wolf Foundation is headquartered. "I ordinarily wouldn't have even answered the call, but now I answer everything because I'm afraid it might have something to do with the fire remediation work being done at our house in Altadena." The Wolf Prize includes both a commendation and a $100,000 monetary award.